Naturalistic lighting

At Rigshospitalet Glostrup, in Copenhagen, Dr. Anders Sode West and his colleagues set out to evaluate the effect of naturalistic, or circadian, lighting on post-stroke patients admitted for rehabilitation: the first study of its kind to investigate the influence of systematic, sunlight-based light on recovering patients. In simple terms, “naturalistic light” is artificial light that replicates nature’s own rhythm of darkness and light. It also supports our circadian rhythm: the human brain’s 24-hour internal clock for cycling through sleepiness and alertness at regular intervals.

The predictability of the natural rhythm of light optimises our physiology, health and behaviour. But for the majority of us, who might spend as much as 90% of our time indoors, that natural daily rhythm can be elusive.

Getting sufficient daylight under modern living conditions is challenging enough. But in a controlled environment, such as a hospital or rehabilitation centre, maintaining a healthy circadian rhythm becomes particularly challenging, especially for long-term patients.

So, what can healthcare institutions do to create an environment that supports a healthy biorhythm and reduces complications? And, on a broader scale, what can all our interiors – from our homes and workplaces to our schools and public spaces – do to compensate for our severed connection to nature?

Illumination that mimics nature

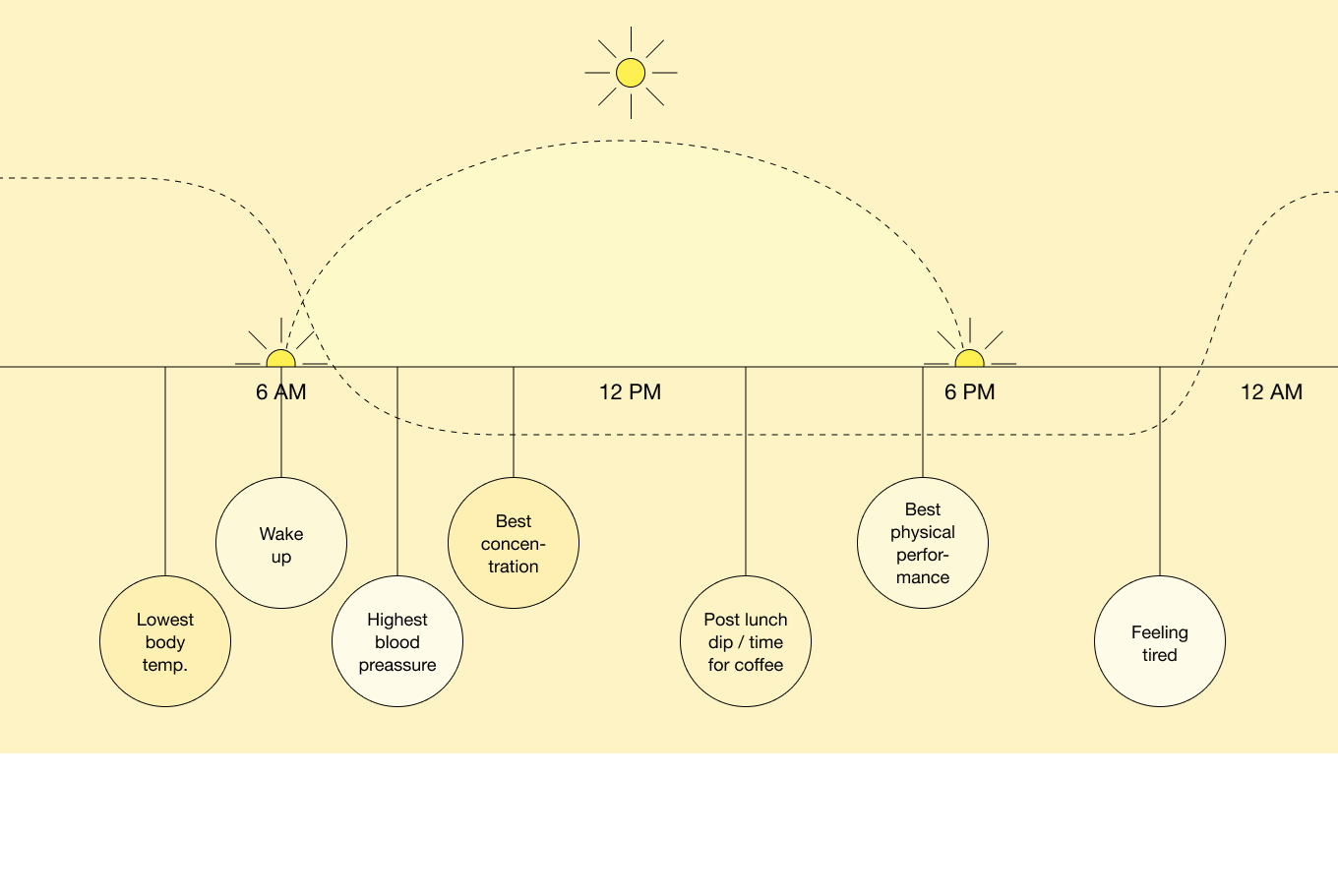

To best support the human circadian rhythm, naturalistic indoor lighting copies the rhythm of sunlight, replicating natural fluctuations in darkness and light (lux), colour (kelvin), and spectrum (wavelength).

“Our brains read the light to estimate the time of the day,” explains Dr. West. “It is therefore crucial to get the right light at the right time, so the organs and the brain can speed up or slow down their activity at the right time. We know that all cells in our body are circadian-controlled – and that 10-15% of our genes are directly controlled by the master clock in the brain’s hypothalamus. And we know that a disturbed circadian rhythm is associated with endocrinological disturbances (for instance, Type 2 diabetes), cognitive impairment, sleep problems, depression, and cancer, among other things.”

A bright antidote to depression and fatigue

After a stroke, the most frequent complications include a depressive mood, decreased sleep quality, and fatigue: symptoms that can negatively impact cognitive function, functional recovery, quality of life – and, ultimately, a patient’s survival. To evaluate the effects of dynamic, naturalistic lighting, Dr. West’s team installed multi-coloured, LED-based luminaries in the intervention unit. A computer controlled continuous changes in colour, brightness and spectrum over 24 hours. At night, the light was turned off completely and, when needed, turned on with negligible blue wavelengths to minimise disturbance. The control group in the study, on the other hand, was placed in rooms with standard indoor lighting. The intervention unit of 39 patients and the control group of 32 were observed over the course of one year to include all four variances of seasonal light.

“We found that both depressive mood and fatigue were significantly lower in the intervention group at discharge compared with the control group,” says Dr. West. “Depressive mood was between 32% and 49% lower, while fatigue was, on average, 21% lower.”

At discharge, the patients exposed to naturalistic light also had significantly increased melatonin levels in their blood, and an evolved melatonin rhythmicity, which is closely tied to a healthy circadian rhythm and healthy sleeping patterns. The findings join a growing body of research on the profound effect that research-based, circadian lighting can have on wellness in the modern world – and inspire further exploration of its potential.

Research-based lighting design

As we examine the design changes in the healthcare sector, it’s worth noting that while circadian lighting may be the optimal solution, there is still much to be said for working with the decorative lighting at our disposal. After all, it’s not just the light itself that matters, but also the form in which it is delivered. For instance, the PH Wall lamps recently installed in the corridors of a hospital in Esbjerg, Denmark have lent the space a warmth that’s a welcome break from traditional, bright overhead lighting.

At Frederiksberg Hospital in Copenhagen, Louis Poulsen has contributed lighting to test rooms designed to help patients recover faster and to create a more pleasant environment for patients, staff and visitors. Designed by KHR Architecture, these LP Circle fixtures are Kelvin-adjustable and feature integrated ventilation. With more daylight, circadian lighting, a more patient-friendly colour scheme, and single-patient rooms, the design team hopes to enhance not only ambience, but also outcomes. In Seinäjokim, Finland, Louis Poulsen has been involved in another project where Kelvin-adjustable LP Circle fixtures have been installed in intensive care rooms to expedite patient recovery.

Other examples of patient-friendly illumination abound. A research team at Bispebjerg Hospital in Copenhagen is investigating light’s effect on depressive patients and has installed naturalistic lighting at the psychiatric department. The St. Augustinus Memory Centre in Neuss, Germany has been experimenting with human-centric lighting to help treat patients with dementia. Meanwhile, across the ocean at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, a clinical trial is testing whether brighter morning light in cancer patients’ rooms can reduce fatigue and depression. And in the paediatric intensive care unit of University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital, the lighting mimics daylight to reduce disturbance to the young patients’ circadian rhythm.

Dr. West’s vision that “the light of the future is going to reflect the time of day” might be closer than we realise – and not just in healthcare. If a patient can go home sooner, and in a better state, thanks to the artificial light in the hospital room, one can imagine the benefit such lighting can bring to an entire society that spends far more time indoors than nature intended. Of course, circadian light is not a cure-all. But all signs point to it being a key component not only on the road to recovery, but also in our general pursuit of happiness and wellness.